So what does the band’s music share with the music played within the commune? After a pause, Goatman replies: “It’s not the same. It can be whatever, but music is pretty free up there. There’s lots of [styles]. Like in the ’70s there was prog rock, probably, but in the ‘80s, I don’t know, actually – but still it’s a lot of instruments, a lot of drums, lots of rhythms, lots of dancing, lots of like pretty natural, natural…” he trails off, searching for the right word. “Natural music. You know what I mean?” laughing, “Natural music is not the right word… it’s a stupid word but… don’t write natural music…” I did, but only because I think the term is probably more precise than Goatman feels: the Goat commune and its music seems oriented around an ideology of authenticity, of music and expression arising organically from unconstrained self- and group-expression, free from pretence or individualism.

“Like, simp… not simple music” – still struggling for the best description – “But people play together, you know, jamming with drums maybe. Or the next day, people jamming with drums and a guitar. It doesn’t really matter. Mostly jamming but they pop up like bands or stuff like that – groups that want to do their own music like we have done. And then some young people from up north moved to Gothenburg and hooked up with me and some other people and… So it’s not just people from here influenced by other music. It can be punk rock or whatever, you know. So influences are brought in, it’s the openness for it that is the thing, in a way. You mix whatever you like with whatever you like in the songs and it’s your own expression.”

I mention that there seems to be a subtle, and paradoxically constructive, interaction between tradition – in the commune’s approach to collective music making – and the erasure of tradition – in the desire to incorporate sounds from elsewhere. “Yeah,” he agrees. “I would say that [the latter] is the musical tradition, basically. That is what the tradition is: to stay open, to travel, to explore, you know. To explore cultures and music and, if you feel something appeals to you, use it: it’s yours. That’s the tradition, maybe, in a way.”

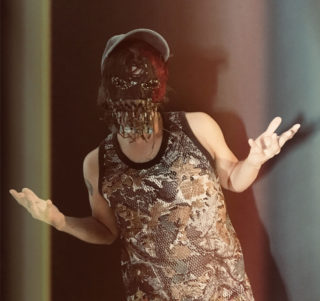

And it’s this goal of forging a purity of musical expression – one which arises from the spontaneous and egoless meeting of individuals – that drives Goat’s desire for anonymity. “When we play together wearing masks, wearing something that expresses our sense of the music, we feel more united, we feel more like one person,” Goatman tells me. “It’s more easy. It’s more easy to express something when you know that your face is not there, when your identity is not there. It’s just music coming out. It’s easier to let it out, because there are people watching you.

“And, yeah, it’s also about the individualism of our time because it’s that individualism that we want to get away from. You know, we’re not individuals, Goat is not consisting of individuals.” He pauses briefly and laughs. “It is of course consisting of individuals but it’s not the way we want to be seen, that’s what I mean.”

It’s almost as if the anonymity is a form of secular sacrifice, of the individual to the larger group, I suggest.

“Yeah, I agree with it, yeah,” says Goatman. “It’s a hard word to use, but at the same time I think it’s pretty correct. That’s what Goat is mainly about: you have to give up something for the greater good of the group, of the collective or the commune or whatever. We give up: it’s for the music in a way.”

Goat’s anonymity, then, is an integral part of the group’s self-concept as a commune, allowing the individual to surrender their ego, their desire for ownership or recognition.

“Exactly,” he concurs. But then, in a characteristically self-contradictory move, he adds: “And also, you know, you can’t forget that a show is a show.” His laugh punctuates and halts his train of thought. Refraining from elaboration, Goatman merely leaves the statement to hang briefly between us in all its opacity and knowing ambiguity. After a pause, he adds simply: “That’s also true.”