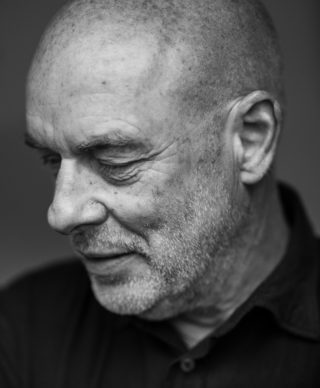

As you may expect from Eno, there is something deeper and more profound to be extracted from the creative process of working on these projects. “Simple algorithms produce very unexpected, very unpredictable results,” he tells me. “One of the reasons I like them is because they tell you why the world is so complex.” He continues as he becomes more animated and excited and a quick flash of his gold tooth cracks through his smiling mouth. “When you see a few simple rules operating together to produce these amazingly elaborate worlds of things, you think ‘bloody hell, that’s only three simple rules’ you could write this down in a paragraph and yet all this stuff comes out of it.” He then continues without pause into another world of conversation altogether.

“There’s a whole group of people in the world – many of them in America – who can’t believe that the complexity of the universe is possible without postulating a god, but I can pretty much prove that it is. You don’t have to be involved with this thing for very long to see how complexity arises out of simplicity – that was the big perception of Darwin. The most important thing to come from Darwin, that great scientist, was that he showed the history of evolution is the progression from simplicity to complexity and this is quite the opposite of what religious people think – they think God is the most complex thing and therefore God can create less complex things. This is not true. This is provably not true. I think in eight and a half minutes I could convince any creationist that they have got the wrong end of the stick.” It’s a little tangent that gives an insight into Eno’s clear love of all things scientific and provable and one also suspects that when he says “eight and a half minutes” it’s not some arbitrary figure plucked from obscurity and more a recorded time of his very precise argument made.

Brian Eno’s discovery of ambient music is a relatively well-known one. When recovering from being hit by a taxi and bedridden, a friend of his brought him an album of 18th century harp music to listen to. He hobbled to the record player and put it on but once back in bed Eno quickly realised the volume was irritatingly low and he couldn’t hear it properly. Unable to get up again due to the pain he kept it on but this soon led to an epiphany. “This presented what was for me a new way of hearing music, as part of the ambience of the environment just as the colour of the light and the sound of the rain were parts of that ambience,” he said in 1975 when he released ‘Discreet Music’, his first step into ambient. In a startlingly prolific year he also managed to create his pop masterpiece in ‘Another Green World’, release the collaboration album with Robert Fripp, ‘Evening Star’, and produce Gavin Bryars’ ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’, as well as other production credits. In 1978 his ambient leaning had gone full tilt with the releases of ‘Music for Airports’ and ‘Music for Films’. In the linear notes to ‘Music for Airports’ Eno described ambient music as “intended to induce calm and a space to think. Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

I ask him if his own definition of the genre has changed over the years? “I’m quite happy for it to have expanded,” he says. “It now seems to cover all sorts of things, many which I wouldn’t recognise as ambient.” He laughs, and continues. “But I don’t mind. I don’t think I own the definition. I was trying to describe what I was doing, what other people choose to do is different and surprising and very wonderful if they choose to use that name. I’m not proprietorial about it at all.” Given his role as the appointed godfather of the genre, I ask whether he ever feels any sense of pressure or even duty when operating in this area? “No, no…” he stops himself for a minute and strains to think, asking himself, “Do I feel pressure?” before reaching a conclusion swiftly afterwards, “ No, I don’t actually. This is a very nice area of music for me because it very much feels like my field and I can plant whatever I like in it, I don’t really care whether it doesn’t sound dramatically different from anything else that I’ve done before. I just want to keep finding these new colours – mood colours if you like – and seeing what you can do with them.”

Similarly, Eno set out what was something of a mission statement early on in his career that he was a non-musician, unable to play instruments properly and unable to read and write music. Has he had to forcibly stop himself from becoming accomplished in this area? “I think it’s a little bit like that but rather than actively avoiding something, what I’ve been doing is wanting to find a way of defeating my own habits. What happens with anyone who plays anything is that you get into a certain habit, your taste is a habit, it’s a habit of things you like as opposed to things you don’t. So what these processes do [in generative music] is they start doing things that are beyond the envelope of your taste. You think ‘oh this is horrible’ or you think ‘oh that’s very unusual, I wouldn’t have done that but I like it’, so it sort of keeps extending the envelope of what you’re operating in. That’s what I like about them. I like to be put into a situation where I am surprised by the music.”

Eno’s fascination with new terrain is clear but in the world of reforming bands, group’s playing classic albums in full and a general air of nostalgia hovering over a great deal of the music industry like a murky rain cloud, is he approached about such things himself? Is he nostalgic in anyway whatsoever? “I don’t think back that much really,” He says clearly and exactly. “I hardly ever listen to my old work and when I do I always think ‘I don’t even know who did that’, I don’t recognise the person who did it very often, I don’t know how I got to it. So to remake it would be as difficult as remaking a Snoop Dogg song – it’s as unfamiliar to me, really. I would go back to it and think, ‘how do you even play this?’ I have no idea. I’m not tempted by that. It doesn’t mean I never will be but at the moment I see no point in doing it and I have so many new things I want to do – this sort of thing [music playing] I’m fascinated by.”

He tells me that he’s already talking and thinking about his next new project. “I just did a piece last week that is entirely different to anything I’ve done before and I really want to explore it,” he says. “It’s a 13-minute long piece and it sounds like an orchestral piece and I’m going to talk to a friend of mine about potentially scoring it for an orchestra. It sounds like an orchestral piece played on a synthesiser.”